THE

NURSERY

A Monthly Magazine

For Youngest Readers.

BOSTON:

THE NURSERY PUBLISHING COMPANY,

No. 36 Bromfield Street.

1881.

THE NURSERY PUBLISHING COMPANY,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington.

IN PROSE. |

|

| PAGE | |

| The Young Fisherman | 225 |

| A slight Mistake | 227 |

| Two Games | 231 |

| More about "Zip Coon" | 232 |

| Sam and his Goats | 234 |

| Mary's Squirrel | 240 |

| Drawing-Lesson | 241 |

| The Chimney-sweep | 244 |

| Billy and Bruiser | 246 |

| "If I were only a King" | 248 |

| Use before Beauty | 249 |

| Ten Minutes with Johnny | 251 |

| A Cat Story | 252 |

| Tom's Apple | 254 |

IN VERSE. |

|

| The Hen-Yard Door | 228 |

| Toy-Land | 238 |

| A Turtle Show | 242 |

| Two Little Maidens | 247 |

| Summer Rambles | 250 |

| See-Saw (with music) | 256 |

IN PROSE. |

|

| PAGE | |

| The Young Fisherman | 225 |

| A slight Mistake | 227 |

| Two Games | 231 |

| More about "Zip Coon" | 232 |

| Sam and his Goats | 234 |

| Mary's Squirrel | 240 |

| Drawing-Lesson | 241 |

| The Chimney-sweep | 244 |

| Billy and Bruiser | 246 |

| "If I were only a King" | 248 |

| Use before Beauty | 249 |

| Ten Minutes with Johnny | 251 |

| A Cat Story | 252 |

| Tom's Apple | 254 |

IN VERSE. |

|

| The Hen-Yard Door | 228 |

| Toy-Land | 238 |

| A Turtle Show | 242 |

| Two Little Maidens | 247 |

| Summer Rambles | 250 |

| See-Saw (with music) | 256 |

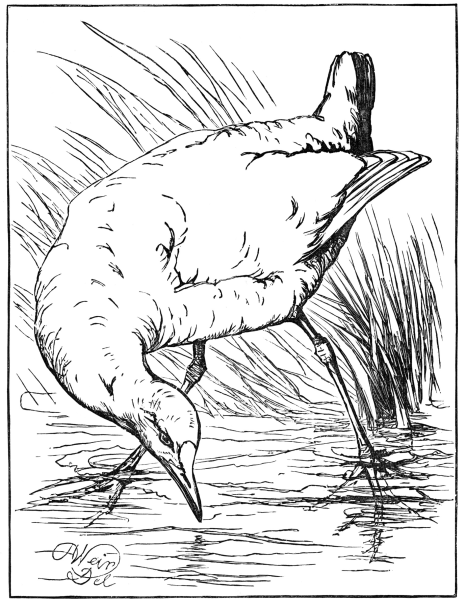

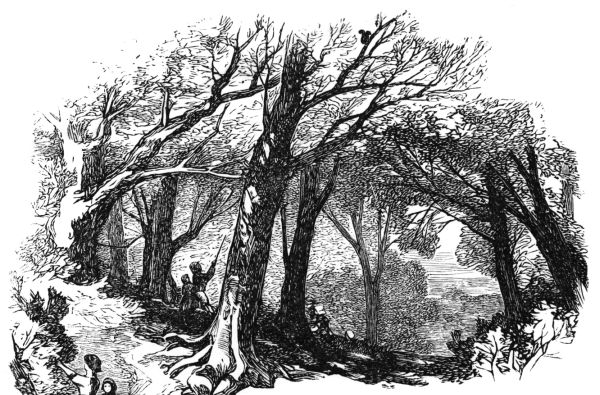

THE YOUNG FISHERMAN.

HEN Charley was eight years old, his father gave him, for a birthday present, a nice fishing-line.

The little boy was greatly pleased. He had fished often in a tub of water with a pin-hook; but now, for the first time, he had a real fishing-line and pole, and was able to go a-fishing in earnest.

The very first pleasant day, he got leave from his father to go to the pond and try his luck.

"Be sure to bring home a good mess of fish, Charley," said his father.

"Oh, yes! papa," said Charley, and with his fishing-pole on his shoulder out he went.

What fun it was! First he dug some worms for bait; then he baited his hook nicely; then he took his stand on a little platform, made on purpose for the use of fishermen, and threw out his hook.

There he stood, in the shade of the old willow-tree, and waited for the fish to bite. As he looked down into the calm, clear water, he saw a boy, just about his own size, looking up at him. He had no other company.

He kept close watch of the pretty painted cork, expecting every moment to see it go under water. But for a long, long time it floated almost without motion.

Charley's patience began to give out. "I don't believe there are any fish here," thought he. Just then the cork dipped a little on one side. Then it stopped. Then it dipped again.

"Hurrah!" said Charley, and he pulled up the line with a jerk. Was there a fish on it? Not a bit of one. But the bait was all gone.

"Never mind!" said Charley, "I'll catch him next time." He baited the hook, and threw it out again. The sport was getting exciting.

Pretty soon the cork bobbed under, as before. "Now I have him!" said Charley. He pulled up once more, and this time with such a jerk that he tossed the hook right over his head, and it caught in the weeds behind him. But there was no fish on it.

"The third time never fails," said Charley, as he threw[227] out his line again. He waited now until the cork was pulled clear under water; then he lifted it out, without too much haste, and, sure enough, he had caught a fish.

How long do you suppose it had taken him to do it? Pretty nearly all the forenoon. No matter! he had one fish to carry home, and he had had a real good time besides.

Charley has caught many a mess of fish since then; but I doubt if he has ever enjoyed the sport more than he did in catching that one fish.

THE YOUNG FISHERMAN.

HEN Charley was eight years old, his father gave him, for a birthday present, a nice fishing-line.

The little boy was greatly pleased. He had fished often in a tub of water with a pin-hook; but now, for the first time, he had a real fishing-line and pole, and was able to go a-fishing in earnest.

The very first pleasant day, he got leave from his father to go to the pond and try his luck.

"Be sure to bring home a good mess of fish, Charley," said his father.

"Oh, yes! papa," said Charley, and with his fishing-pole on his shoulder out he went.

What fun it was! First he dug some worms for bait; then he baited his hook nicely; then he took his stand on a little platform, made on purpose for the use of fishermen, and threw out his hook.

There he stood, in the shade of the old willow-tree, and waited for the fish to bite. As he looked down into the calm, clear water, he saw a boy, just about his own size, looking up at him. He had no other company.

He kept close watch of the pretty painted cork, expecting every moment to see it go under water. But for a long, long time it floated almost without motion.

Charley's patience began to give out. "I don't believe there are any fish here," thought he. Just then the cork dipped a little on one side. Then it stopped. Then it dipped again.

"Hurrah!" said Charley, and he pulled up the line with a jerk. Was there a fish on it? Not a bit of one. But the bait was all gone.

"Never mind!" said Charley, "I'll catch him next time." He baited the hook, and threw it out again. The sport was getting exciting.

Pretty soon the cork bobbed under, as before. "Now I have him!" said Charley. He pulled up once more, and this time with such a jerk that he tossed the hook right over his head, and it caught in the weeds behind him. But there was no fish on it.

"The third time never fails," said Charley, as he threw[227] out his line again. He waited now until the cork was pulled clear under water; then he lifted it out, without too much haste, and, sure enough, he had caught a fish.

How long do you suppose it had taken him to do it? Pretty nearly all the forenoon. No matter! he had one fish to carry home, and he had had a real good time besides.

Charley has caught many a mess of fish since then; but I doubt if he has ever enjoyed the sport more than he did in catching that one fish.

A SLIGHT MISTAKE.

A donkey walking with a lion, fancied himself a lion also, and pretended not to know his own brother.

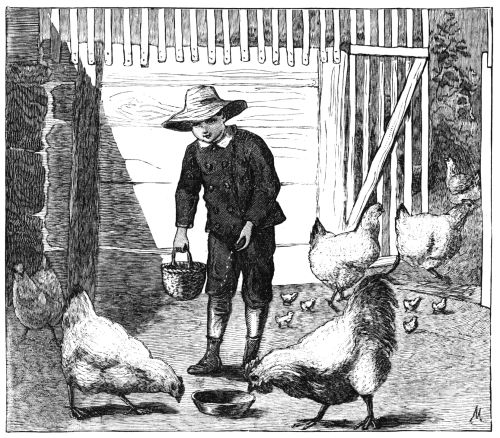

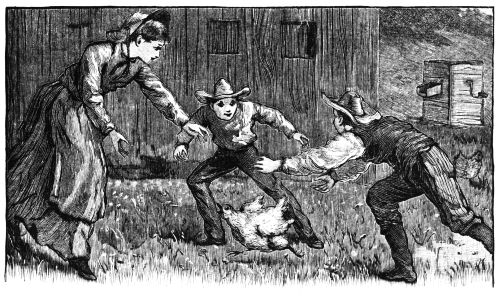

THE HEN-YARD DOOR.

A SLIGHT MISTAKE.

A donkey walking with a lion, fancied himself a lion also, and pretended not to know his own brother.

THE HEN-YARD DOOR.

He did not shut the door;

Out came the rooster and the hens;

Out came the pullets four;

Out came old Speckle-wings, with six

Bewitching little Bantam chicks.

At once the hens began to cluck,

The cock began to crow,

And here and there, and everywhere,

[229]They seemed possessed to go;

They pecked the turnips; in a patch

Of spinach they began to scratch:

And when to drive them in we tried

They straightway to our neighbors hied.

Was just with grass-seed sown;

Upon our left, a garden-plot

With pinks and lilies shone.

In rushed our right-hand neighbor's son,

With flaming face, and said,

"'Shut up your hens,' my father says,

Or he will shoot them dead."

Our left-hand neighbor wrote a note,—

"I all the spring have toiled

To rear the lovely flowers I find

[230]Your roving fowls have spoiled."

To get them home, the livelong day

We tried, till evening gathered gray:

Then back to roost returned the cock,

But some were missing from his flock.

Four hens were with him; where were two?

Perhaps our right-hand neighbor knew!

Back came the pullets, having fed

On dainty pinks, and roses red;

Back came old Speckle; of her six

The cat had caught three little chicks.

We shut the door, and made it fast;

We all were glad the day was past:

We'd lost our hens, and lost our friends;

Our neighbors smile no more;

And all because our careless Tom

Forgot to shut the door!

TWO GAMES.

Here is a boy, full ten years old, playing with a peg-top. What a sight! He might find some better game, I should think. Why is he not out of doors playing baseball? He is big enough to use his arms and legs?

This girl could teach him a much better game than peg-top. She is out on the lawn, all ready to play croquet. She will have fun and fresh air at the same time. Those are two things that all girls and boys need.

MORE ABOUT "ZIP COON."

IP COON: he bites!" This is what I told you was printed in large red letters on the door of Zip's house, after he had grown so cross and snappish that he had to be chained up in the wood-shed.

A big countryman came one day with a load of potatoes. Zippy was inside his house, pretending to take a nap. The man saw the printed letters on the little door, and said to himself, "Zip Coon! where is he? I'd like to see him." So he stooped down, and thrust his hand into the house.

You know you can never catch a coon asleep any more than you can a weasel. Zippy's bright little eyes were wide open: so, when the countryman's big hand came bouncing in at the door, Zip, quick as lightning, seized it in his teeth, and gave it a terribly hard bite.

"Goodness, gracious sakes!" cried the man, pulling out his bleeding hand. "What surprisin' chaps them coons be!" He hadn't seen Zippy; but he felt enough of him: so he hurried down cellar with his potatoes, and when he came back had the empty bag wound about his smarting hand.

Zip Coon was very fond of raw eggs. He would take one up in both his hands, and pound it down hard on the wood-house floor. This would crack the shell. Then he would turn the egg around, hold it to his mouth, and suck the inside out, just as you would suck an orange. After he had sucked the shell clean, he would put one little hand inside, scrape the empty shell, and then lick his fingers so as to eat every bit of the egg-meat.

One day, Isabella's sister Ellen gave Zippy a nice, large, fresh egg. He was very glad to get it, you may be sure, and ate it as I have told you. Then he wanted another,[233] just as you sometimes want another orange. So he took hold of Ellen's hand with one of his hands, and with the other felt way up her sleeve and peeped up with his sharp eyes.

When he found no egg in the sleeve he was angry. He looked up in Ellen's face in a very wicked way, then stooped down and buried his teeth in her wrist. Then he turned and ran into the house, clanking his chain after him.

Zippy was not always so wicked as this, even after he had to be chained up; but he was very mischievous. Once, the[234] servants in the kitchen heard a terrible racket in the wood-house. They went out there and found Zippy on a high shelf where the blacking-brushes were kept. He was throwing the blacking-boxes and brushes down, as fast as he could, and there they lay scattered about the floor. His chain was so long, that he had climbed up on the shelf and was having a good time.

But, after a while, Zip Coon became so fierce that Isabella didn't know what to do with him. She was afraid he would do something terrible to somebody: so she gave him to a man who carried him way off where Isabella and her sisters never saw him any more. And this is all I have to tell you about Zip Coon.

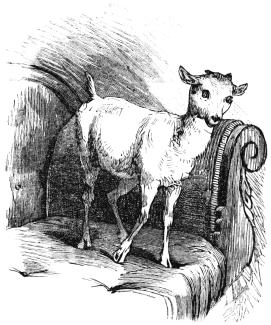

SAM AND HIS GOATS.

AM was a boy about five years old. He lived in the country, and had a nice little black-and-tan dog, Jack, to play with him. Sam wanted a goat. He thought that if he could only have a goat, he would be perfectly happy.

One day, when Sam was playing in the yard, his papa came driving home from town, with something tied in the bottom of the wagon. When he saw Sam, he stopped the horse and called, "Sam, come here, I have something for you."

Sam ran there as fast as he could, and—what do you think?—papa lifted two little goats out of the wagon, and put them down on the ground. One goat was black and one was white. Sam was so glad he did not know what to to do. He just jumped up and down with delight.

Then the dog Jack came running out to see the goats[235] too; but he did not like them much. He barked at them as hard as he could; but the goats did not mind him at all.

Pretty soon mamma came to see what Sam had. When she saw the goats, she said, "Why, papa, what will become of us if we have two goats on the place?" But she was glad because Sam was glad; and Sam gave his papa about a hundred kisses to thank him for the goats.

For some weeks, the goats ran about the yard, and ate the grass; and Sam gave them water to drink, out of his little pail, and salt to eat, out of his hand. He liked to feel their soft tongues on his hand as they ate the salt. The goats would jump and run and play, and Sam thought it was fine fun to run and play with them. Jack would run too, and bark all the time.

Zippy was not always so wicked as this, even after he had to be chained up; but he was very mischievous. Once, the[234] servants in the kitchen heard a terrible racket in the wood-house. They went out there and found Zippy on a high shelf where the blacking-brushes were kept. He was throwing the blacking-boxes and brushes down, as fast as he could, and there they lay scattered about the floor. His chain was so long, that he had climbed up on the shelf and was having a good time.

But, after a while, Zip Coon became so fierce that Isabella didn't know what to do with him. She was afraid he would do something terrible to somebody: so she gave him to a man who carried him way off where Isabella and her sisters never saw him any more. And this is all I have to tell you about Zip Coon.

SAM AND HIS GOATS.

AM was a boy about five years old. He lived in the country, and had a nice little black-and-tan dog, Jack, to play with him. Sam wanted a goat. He thought that if he could only have a goat, he would be perfectly happy.

One day, when Sam was playing in the yard, his papa came driving home from town, with something tied in the bottom of the wagon. When he saw Sam, he stopped the horse and called, "Sam, come here, I have something for you."

Sam ran there as fast as he could, and—what do you think?—papa lifted two little goats out of the wagon, and put them down on the ground. One goat was black and one was white. Sam was so glad he did not know what to to do. He just jumped up and down with delight.

Then the dog Jack came running out to see the goats[235] too; but he did not like them much. He barked at them as hard as he could; but the goats did not mind him at all.

Pretty soon mamma came to see what Sam had. When she saw the goats, she said, "Why, papa, what will become of us if we have two goats on the place?" But she was glad because Sam was glad; and Sam gave his papa about a hundred kisses to thank him for the goats.

For some weeks, the goats ran about the yard, and ate the grass; and Sam gave them water to drink, out of his little pail, and salt to eat, out of his hand. He liked to feel their soft tongues on his hand as they ate the salt. The goats would jump and run and play, and Sam thought it was fine fun to run and play with them. Jack would run too, and bark all the time.

But by and by Sam began to get tired of his goats, and his mamma was more tired of them than Sam was. They ate the tops off of her nice rose-bushes; they ran over her flower-beds; and one day, when the door was open, one of them ran into the parlor and jumped up on the best sofa.

Mamma said this would never do: so the next day papa found a man who said he would give Sam fifty cents for the[236] white goat. As Sam wanted to buy a drum, he was glad to sell the goat; and with fifty cents in his pocket he felt very rich.

Then the other goat was put in the orchard, and he liked it there very much. He liked to have Sam come and play with him. As soon as he saw Sam coming, he would run to meet him, and push him with his head, in play, and try to jump on him.

The goat grew very fast,—much faster than Sam did; so that soon he was quite a big goat, while Sam was still a very small boy. He got to be so much stronger that Sam, that Sam was a little afraid of him.

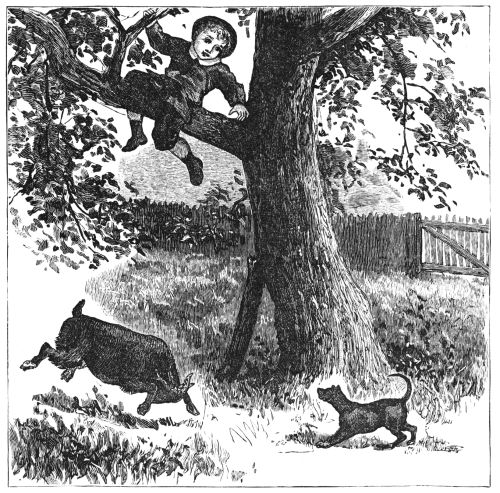

One day, when they were playing, the goat hit Sam with his head, and knocked him down. Sam was scared. He got up, fast as he could, and tried to run to the gate; but the goat ran after him, and Sam had to climb into a tree. It was a nice apple-tree. Sam had often sat up there before, and liked it; but, now that he was forced to sit there, he did not like it at all.

The goat staid at the foot of the tree, and, when Sam tried to come down, he would shake his head at him, as if to say, "Come down if you dare." Sam did not dare. "Oh, dear!" said he, "what shall I do?"

There were some green apples on the tree; and Sam thought, that, if he threw them at the goat, he could drive him away: so he began to pick the apples, and throw them at the goat.

The first one hit the goat right on his head; but it did not hurt him at all. He just went to where the apple lay, and ate it up; and every time that Sam threw an apple at him the goat would eat it, and then look at Sam, as if to say, "That is good. Give me some more."

At last Sam said, "Oh, you bad, bad goat! I wish you would go away. If you don't go away, I'm afraid I shall cry." Then he thought of Jack, and called, "Here, Jack! Here, Jack!" Jack came running up to see what Sam wanted. Sam said, "At him, Jack! At him, Jack!"

Jack ran at the goat, and barked at him and tried to bite him; but the goat kept turning his head to Jack, so that[238] Jack could not get a chance to bite him. At last the goat got tired of hearing Jack bark, and thought he would give him one hard knock, and drive him away.

So he took a step or two back, and then ran forward, as hard as he could, to hit Jack. But, when his head got to where Jack had been, Jack was not there: he had jumped away. The goat was going so fast, that he could not stop himself, but tumbled over his head, and came down on his back with his legs sticking up in the air.

Sam laughed so hard that he almost fell out of the tree, and Jack was so glad, that he jumped and barked, and tried to bite the goat's legs. At last the goat got up and walked over to the other side of the orchard as far as he could go. Then Sam jumped down out of the tree, and ran to tell his mamma all about it.

TOY-LAND.

To all little people the joy-land.

Just follow your nose,

And go on tip-toes:

It's only a minute to Toy-land.

And oh! but it's gay in Toy-land,—

This bright, merry girl-and-boy-land;

And woolly dogs white

That never will bite

[239]You'll meet on the highways in Toy-land.

Society's fine in Toy-land;

The dollies all think it a joy-land;

And folks in the ark

Stay out after dark;

And tin soldiers regulate Toy-land.

There's fun all the year in Toy-land:

To sorrow 'twas ever a coy-land;

And steamboats are run,

And steam-cars, for fun:

They're wound up with keys down in Toy-land.

Bold jumping-jacks thrive in Toy-land;

Fine castles adorn this joy-land;

And bright are the dreams,

And sunny the beams,

That gladden the faces in Toy-land.

How long do we live in Toy-land?—

This bright, merry girl-and-boy-land;

A few days, at best,

We stay as a guest,

Then good-by forever to Toy-land!

The first one hit the goat right on his head; but it did not hurt him at all. He just went to where the apple lay, and ate it up; and every time that Sam threw an apple at him the goat would eat it, and then look at Sam, as if to say, "That is good. Give me some more."

At last Sam said, "Oh, you bad, bad goat! I wish you would go away. If you don't go away, I'm afraid I shall cry." Then he thought of Jack, and called, "Here, Jack! Here, Jack!" Jack came running up to see what Sam wanted. Sam said, "At him, Jack! At him, Jack!"

Jack ran at the goat, and barked at him and tried to bite him; but the goat kept turning his head to Jack, so that[238] Jack could not get a chance to bite him. At last the goat got tired of hearing Jack bark, and thought he would give him one hard knock, and drive him away.

So he took a step or two back, and then ran forward, as hard as he could, to hit Jack. But, when his head got to where Jack had been, Jack was not there: he had jumped away. The goat was going so fast, that he could not stop himself, but tumbled over his head, and came down on his back with his legs sticking up in the air.

Sam laughed so hard that he almost fell out of the tree, and Jack was so glad, that he jumped and barked, and tried to bite the goat's legs. At last the goat got up and walked over to the other side of the orchard as far as he could go. Then Sam jumped down out of the tree, and ran to tell his mamma all about it.

TOY-LAND.

To all little people the joy-land.

Just follow your nose,

And go on tip-toes:

It's only a minute to Toy-land.

And oh! but it's gay in Toy-land,—

This bright, merry girl-and-boy-land;

And woolly dogs white

That never will bite

[239]You'll meet on the highways in Toy-land.

Society's fine in Toy-land;

The dollies all think it a joy-land;

And folks in the ark

Stay out after dark;

And tin soldiers regulate Toy-land.

There's fun all the year in Toy-land:

To sorrow 'twas ever a coy-land;

And steamboats are run,

And steam-cars, for fun:

They're wound up with keys down in Toy-land.

Bold jumping-jacks thrive in Toy-land;

Fine castles adorn this joy-land;

And bright are the dreams,

And sunny the beams,

That gladden the faces in Toy-land.

How long do we live in Toy-land?—

This bright, merry girl-and-boy-land;

A few days, at best,

We stay as a guest,

Then good-by forever to Toy-land!

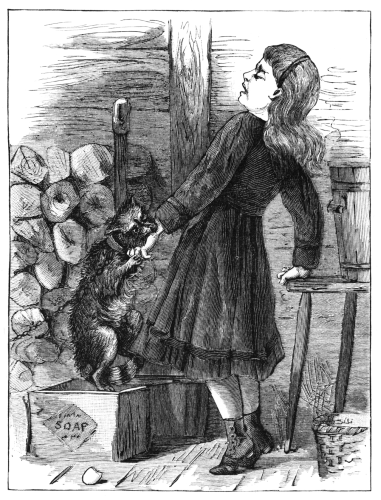

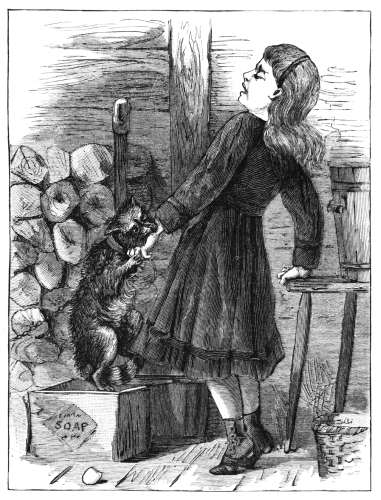

MARY'S SQUIRREL.

WANT to tell you about the little squirrel we have. His name is Frisky. He came from New Jersey, and was quite tame when we got him. We thought it would be better to let him out in the fresh air among the trees; so we let him out.

I was away at aunt Lizzie's; but I came home early. Just as Henry and I were going to bed,—Henry is my brother,—the cook called me, and, of course, Henry came after me to see what was the matter.

I could not understand what it was at first; but pretty soon I saw it was Frisky up in one of the trees on our place. Frisky never bites: so it was not much trouble to catch him.

All the servants were there; but they could not catch him, because he did not know them: so I made them stand back, and held out a peanut to him. He came down and ate it; then he trusted me, and came down and ate another. As soon as I got him within reach, I seized him and gave him to William, the gardener, who, while I held the door open, popped him into his cage. I am eight years old, and my name is

VOL. XXX.—NO. 2.

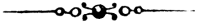

A TURTLE SHOW.

Along the shore in a golden row,

Is a single rock with its mossy ridge,

And a log as mossy, resting there

Half in the water, and half in the air,

From shore to islet a beautiful bridge;

And the lily-pads on either side

Might tempt the little green frogs to ride;

And the lily-blooms, so purely made,

Do tempt the little white feet to wade.

What do you think I saw one day

In the month of June, as I passed that way?

Five little turtles, all in a row,

On the top of the log,—a funny show,—

For they carried their houses on their backs,

And tucked their toes out through the cracks

Under the eaves! while their heads and tails

Played hide-and-seek behind the scales.

They had golden dots on every shell;

And they stood so still, and "dressed" so well,

You might think they were called up to spell;

And a "master" turtle, big and brown,

[243]On the top of the rock sat looking down

In a learned way, as you might say

To "put out words,"—and perhaps 'twas so,

Though I heard no word,—but this, I know,

The five little heads looked so very wise

With their little bead eyes, they must have heard

If ever the master pronounced a word.

VOL. XXX.—NO. 2.

His parents died when he was very small, and he was bound out to a master, who taught him how to clean chimneys. Jacob did not like the work at first, and was[245] afraid to go up the chimney; but now that he has got used to it, he likes it quite well. He sometimes sings a merry song while he is at work.

Mary's mother has sent for him to come and clean out her chimney; for it is choked up with soot, and she cannot make her fire burn.

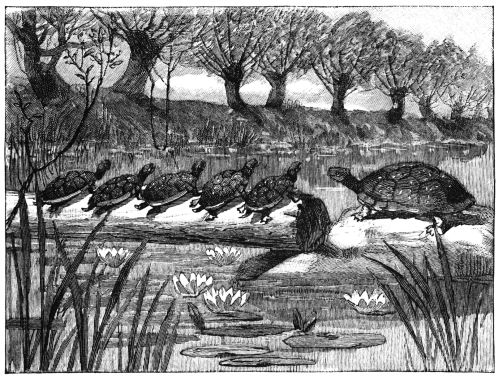

BILLY AND BRUISER.

ILLY is a small boy: Bruiser is a big dog. They are great friends. Billy gets on Bruiser's back, and treats him as if he were a horse.

Bruiser takes this as a good joke. He likes to have Billy play with him in this way. But it would not be safe for anybody else to do it.

Bruiser is a grand watch-dog. One day the old dog gave a fierce growl to keep off a butterfly.

He thought the butterfly was going to attack Billy. Billy had a good laugh at this; for, small as he is, he thinks he is a match for a butterfly.

TWO LITTLE MAIDENS.

|

This little maiden is out for a walk,

A fair little maiden is she; And I really believe she is having a talk With a bird flying down from a tree. She asks him to tell of his home in the woods; He sings of the summer so gay; While a very tall maiden sits by on the grass, And hears every word that they say. |

"IF I WERE ONLY A KING."

ONE fine, warm, summer day, four children were playing together in the garden.

"Oh!" said one of them, "if I were only a king, I would live in a beautiful castle that should reach up to the clouds."

"And I," said another, "would wear nothing but gold and silver clothes."

"If I were one," cried a little boy, "I would do nothing but eat cake and pudding all day long."

"And I," said a little girl, blushing, "would give money to all the poor children I saw, so that they might buy food and clothes."

Which of these children do you think would have made the best ruler?

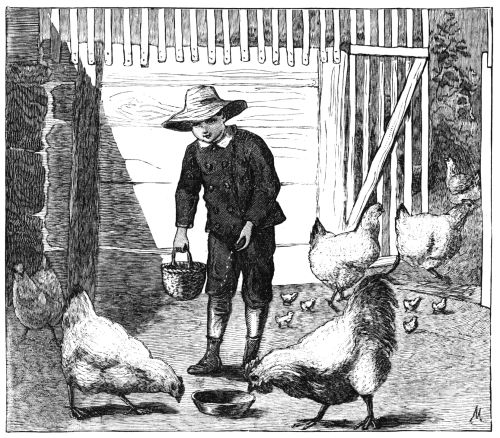

USE BEFORE BEAUTY.

THE hens and turkeys were scratching for their breakfast in front of the barn-door; while the dog lay lazily looking on. The proud peacock stood on the fence near by, and spread his tail out, that the morning sun might shine on it, and make it still more beautiful.

"Ah!" said the peacock to one of the hens, "do you not wish that you were as handsome as I am? Then you would never have to scratch for your food, but would be fed and taken care of and admired."

"I wish nothing of the kind," said the hen. "There is something which men prize more than beauty, and that is usefulness. If I were as fine and gay as you are, men would miss the eggs I lay."

"That is just my view of the case," said a goose. "If I were not a goose, I should like to be a hen. I would not be a lazy peacock."

"She is quite right," said the dog. "You are very beautiful to look at, Master Peacock, but that is all you are good for. Take comfort in your fine feathers, but don't boast."

USE BEFORE BEAUTY.

HE hens and turkeys were scratching for their breakfast in front of the barn-door; while the dog lay lazily looking on. The proud peacock stood on the fence near by, and spread his tail out, that the morning sun might shine on it, and make it still more beautiful.

"Ah!" said the peacock to one of the hens, "do you not wish that you were as handsome as I am? Then you would never have to scratch for your food, but would be fed and taken care of and admired."

"I wish nothing of the kind," said the hen. "There is something which men prize more than beauty, and that is usefulness. If I were as fine and gay as you are, men would miss the eggs I lay."

"That is just my view of the case," said a goose. "If I were not a goose, I should like to be a hen. I would not be a lazy peacock."

"She is quite right," said the dog. "You are very beautiful to look at, Master Peacock, but that is all you are good for. Take comfort in your fine feathers, but don't boast."

Where the sheep are straying;

With the birds and butterflies

Let them now be playing,—

In the hollow on the hill,

All the green lawn over,

Through the yellow buttercups,

Down among the clover.

With the sunshine in their hearts,

In their cheeks the roses,

Let them breathe the balmy air,

Let them gather posies.

In the merry month of June,

Summer's fairest weather,

Let the children and the flowers

Bud and bloom together.

TEN MINUTES WITH JOHNNY.

O grandpa's cows chew gum, like Mr. Connor's cows, mamma?" asked Johnny, a few days ago, as he stood emptying his pockets of hay-seed on the dining-room carpet, after a visit to the barn.

"Cuds you mean, don't you, dear?" asked mamma.

"No, gum. Mr. Connor says it's gum; and they're his cows: so he knows."

"No, grandpa's cows chew cuds, like all good grass-eating cows. Perhaps Mr. Connor's cows do not eat grass or hay."

"Yes, they do," said Johnny. "I've seen 'em."

"Well, then," said mamma, "they must chew cuds."

"What are cuds, mamma?"

"Why, after the cow has chewed the fresh green grass or the dry hay in her mouth, she sends it down into a large stomach, to be soaked; then she sends it into another stomach, to be rolled into balls; then up it goes into her mouth again, to be chewed over; and each little ball is a cud."

"Doesn't she have any other stomach for it to go into then, mamma?"

"Yes, two more. Do you have four stomachs, like a cow?"

"No, of course I don't. I don't chew cuds."

"Well, you may get a brush and dust-pan, and brush up that hay-seed from the carpet; then come with me, and I'll show you a picture of a giant kangaroo with her baby in a fur bag."

"Oh! where does she live, mamma?"

"Brush up that hay-seed, then I'll tell you all about her," said mamma. With this promise in view, Johnny hastened[252] to brush up the litter he had made, talking to himself the while, somewhat after this wise,—

"Chew away, old cow! You'll have to keep your big teeth going all night to keep all those stomachs at work. One stomach, two stomachs, three-e-e, four-r-r. All ready, mamma!"

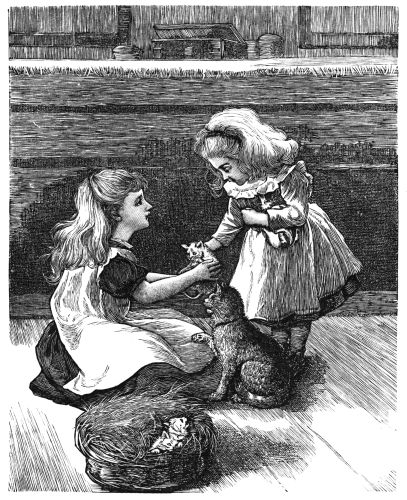

A CAT STORY.

ID you ever see a cat laugh? Look at the cat in the picture, and see if she is not laughing. It is plain to me that she is.

What is she laughing at? Why, that is plain enough too. She is amused at the talk of those two little girls about her kittens.

There are four kittens,—just two for each; but little Jenny wants to take them all up in her arms, though she can hardly hold more than one. This is what pleases the old cat.

Now I am going to tell you a cat story.

Once, when I taught school in the country, I boarded at farmer Clark's house, where there were sixteen cats,—Yes, sixteen cats! There was a big yellow cat, and a big gray cat, and a big black-and-white cat, and lots of little kittens.

The big gray cat was named Gussy. She was the grandmother of them all. She lived in the house. The rest staid around the barn. Farmer Clark was a good man, and did not believe in killing any thing that was not dangerous to life or property. So no little kittens were drowned, if he knew it.

Mrs. Clark taught me how to make butter; and I was told to feed the skimmed milk to the cats. There were two[253] large dish-pans that I used for this purpose. They were shallow and leaky; but precious little time there was for the milk to leak.

As soon as I appeared at the door, and called, "Tom, Tom!" the cats came tumbling, pell-mell, mewing, and rubbing against me. It was a sight to see.

First, there would be a thick row of cats around the pans,[254]—so thick that only sixteen tails and thirty-two hind-legs could be seen. The next minute the heads would go lower, and the fore-paws would go up on the edge of the pans.

Then a kitten would jump in. Then they would all fight, and push, and spit, and snarl to get to the lower side of the pan, where the milk was the deepest.

And then it was all gone. And the pans would be licked clean. And then sixteen tongues licked sixteen jaws, and thirty-two eyes appealed for more. But it was no use to beg. Then sixty-four legs trotted off, and only old Gussy went into the house; while the others went to the barn.

There were no rats or mice around those premises, I tell you. I often wonder how many cats there are at farmer Clark's now. And sometimes I dream about them. This is a true story.

TOM'S APPLE.

"Is he a pretty worm?" asked his mamma, looking up from her sewing.

"Pretty, mamma! Who ever heard of a worm being pretty? No, no! he's a horrid crawling thing. I sha'n't eat any more of the apple. I couldn't, now I've seen him in it."

"Let me see him," said mamma: so Tommy brought the apple to his mother.

"Why, yes, he's a beauty," said she. "Just look at that[255] little red cap he wears, and see how soft and white his skin is. If nobody had picked that apple, he would have spun a little rope from out his body, and let himself down from the high tree, down, down, to the earth.

"Then he would have crawled into a little hole in the ground. When he had covered himself all over with a gray sheet, he would sleep, sleep, sleep. But by and by he would awaken.

"He would come out of the tight shroud, and find that he had airy, gauzy wings with which he could fly: so he would go flitting and fluttering up into the warm sunshine to find an apple-blossom."

"What would he want of an apple-blossom?" asked Tommy, much interested now in his apple-worm.

"Oh, to lay an egg in," said mamma. "And, when the apple-blossoms grew, the egg would be softly wrapped within its pink heart. And when the blossom turned into an apple there would be a tiny baby-worm to feed upon the white pulp. Then some day, perhaps, some other little boy would exclaim, 'Bah! ugh! oh!' about him, as my little boy did just now about the mamma-worm."

"Oh!" said Tom thoughtfully. "I'm glad nobody will have that chance: here goes."

And he tossed the apple, worm and all, out of the window.

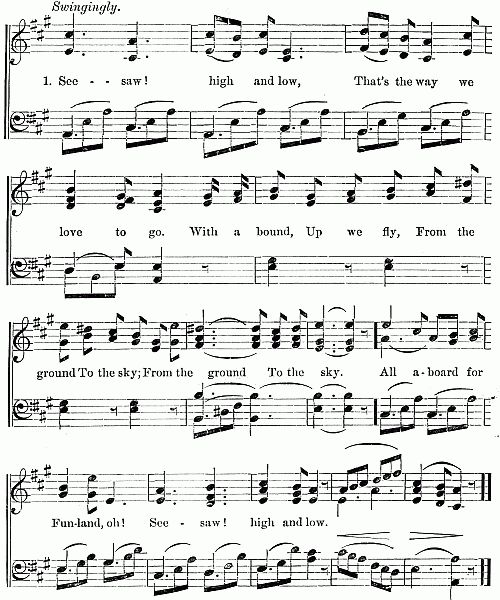

SEE-SAW.

and a larger image of the music sheet may be seen by clicking on the image.]

That's the way we love to go.

With a bound,

Up we fly,

From the ground

To the sky;

From the ground

To the sky.

All aboard for Fun-land, oh!

See-saw! high and low.

2. See-saw! birdies play

On the tree-tops, just this way;

And the bees

Rock the rose,

When they please

With their toes!

And the winds the wavelets blow,

See-saw! high and low.

3. See-saw! oh, what sport!

Wish the days were not so short!

Girls and boys,

Everywhere,

Rosy joys,

Earth so fair!

Gayer playmates do you know?

See-saw! high and low.

Transcriber's Notes

Obvious punctuation errors repaired.

The original text for the July issue had a table of contents that spanned six issues. This was divided amongst those issues.

Additionally, only the July issue had a title page. This page was copied for the remaining five issues. Each issue had the number added on the title page after the Volume number.

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NURSERY, AUGUST 1881, VOL. XXX ***